Hoc pronuntiatum: Ego sum, ego existo, quoties a me profertur, vel mente concipitur, necessario esse verum.

Cette proposition: “Je suis, j’existe”, est nécessairement vraie, toutes les fois que je la prononce, ou que je la conçois en mon esprit.

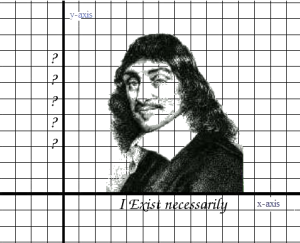

The proposition: “I am, I exist”, is necessarily true each time it is expressed by me, or conceived in my mind. Meditations

Certainty from radical doubt

Having doubted his trust of his faculties of sense, having found no way to be sure he is not dreaming, having admitted that hallucinations and a mind messed up by a malevolent spirit could interfere with his ability to reason, Descartes arrives at his one fixed point, from which he hopes to reestablish a solid foundation for knowledge. Descartes’ elegant writing entices us into his rationalist vision and dramatically sweeps away centuries of scholastic philosophy.

In the second of his meditations Descartes has abandoned the famous “cogito ergo sum” of the Discours sur la méthode. This may be in recognition that rather than advance an argument of syllogistic logic, as implied by the ‘cogito’, Descartes relies on an argument by elimination. When systematic doubt has stripped away the bases for knowledge, he still finds he finds that thought cannot be discarded and that the act of thought defines his existence as “A thinking thing”, “Res cogitans” , “Une chose qui pense”. Critics who say that Descartes has taken a step too far to arrive at the certainty of his own (mental) existence, have missed that the process of elimination has effectively redefined the ‘I’, his own self, as a subject of thought.

Descartes recognises this vanishingly small point of certainty, but the intuition lacks a point of reference; the Cartesian coordinates are incomplete; he is trapped in his subjective, solipsistic existence, in which personal apprehension is all. Is there a way out? Descartes seeks to demonstrate the necessity of the existence of a God, who can provide a divine guarantee of a material, external world. Few would agree that Descartes succeeded.

Can justifications for a deity provide a second coordinate to provide a fixed point from which knowledge can be reconstructed on secure foundations?

Descartes strategically sets out a definition of God: “I understand by the name ‘God’ a certain substance that is infinite, independent, supremely intelligent and supremely powerful”, Descartes then procedes to use this definition as the basis for his arguments that God does exist. In contrast to his radical scepticism, these arguments tend to hark back to the manner of medieval scholasticism.

An immaterial first cause argument

Descartes’ more distinctive argument is a rationalist first cause argument in which causation is applied to the origins of ideas. From Descartes’ conception of God, he asks what could be the cause of this conception. However, although this procedure may function for an idealist, platonic deity, there is no need to accept the assertion of a reality outside the solipsistic bubble.

Descartes is consistent in not using any arguments for the existence of a deity that depend upon perception of the external world. It is this deity that provides the fixed coordinate that validates external, material existence and hence the foundation for the reconstruction of all knowledge.

The ontological argument: by definition, God exists!

Does Descartes present his ontological argument in all seriousness? Apparently so, yet it leaves the impression that he is using quantity of arguments to make up for convincing quality. It is though he is asking us to think of an imaginary friend and then to appreciate the difference if we try to imagine that our imaginary friend is real. Kant’s point that concepts remain as concepts whether they are exist or not; that existence is not a property is well made.

Despite Descartes strenuous efforts, this arguments cannot escape circularity and moreover have the effect of making his rather generic monotheistic God contingent upon Descartes’ own existence. Naturally Descartes tries to deny this and assert that the cause of his existence is God, and Descartes asserts that the bedrock of his philosophy, the clear and distinct idea of his existence is validated by God ex post facto. Nonetheless the insight of his own existence is more convincingly “clear and distinct” than any of Descartes’ justifications for the existence of a deity. The claim that his idea of God is “clear and distinct” because God is good enough to grant him that clarity and distinctiveness in his perceptions, lacks the Euclid inspired, geometrical standards that Descartes had aspired to achieve.

Descartes needs to argue that God exists in order to establish his second coordinate and point of secure reference from which knowledge can be rebuilt. Descartes claims that from his definition of God, that God cannot be a deceiver and is responsible for Descartes’ inability to really believe that an external world does not exist.

Although Descartes is inspirational in the way he clears the philosophical clutter of preceding centuries and sets out a programme for reconstructing knowledge, few, if any, would accept his philosophy as it stands. In particular his justification for why we can know an external material world is at best a provisional hypothesis.

Is there an escape from solipsism? Is there an alternative second coordinate that can establish an external reality?

From a Cartesian perspective, is there another route to escape the subjective, solipsistic bubble? Is there an alternative? Since solipsism is so subjectively self validating and hermetically coherent it seems impervious to attack. Pragmatically, however, it would seem to merit Bertrand Russell’s remark on Leibniz’s Monadology: “a kind of fantastic fairy tale, coherent perhaps, but wholly arbitrary.” Monadology, too, can be viewed as a sophisticated elaboration of Cartesian solipsism. Commenting elsewhere on solipsism, Russell recounts:

“As against solipsism it is to be said, in the first place, that it is psychologically impossible to believe, and is rejected in fact even by those who mean to accept it. I once received a letter from an eminent logician, Mrs. Christine Ladd-Franklin, saying that she was a solipsist, and was surprised that there were no others. Coming from a logician, this surprised me.”

Christine Ladd-Franklin, was a pioneer for the advancement of women in academia, so it is rather sad that I should only be aware of her from this anecdote. Russell goes on to write that although he cannot disprove solipsism, it would be “insincere and frivolous” of him to pretend any credence for it.

Communication implies an external language

The Achilles heel of solipsism is its arbitrariness. If this essay is being read and understood it is because it is being communicated in a common language. In the terminology of semiotics, language functions as a system of signifiers, which are almost always either sounds or visual images, generally in the form of letters organised as words. The signifiers represent the concepts, the referent or the signified. With the possible exception of one or two onomatopoeic words the relationship between the signified and the signifier is completely arbitrary. There is nothing in the letters B, E, A and R placed in that order to logically link them to a large omnivorous mammal nor to the ability to withstand, carry or support something. The association is essentially arbitrary, however when we use these words, we use them with the prior assumption that what the concepts they signify, the signified, are fixed objects that are mutually recognisable to those engaged in communication. Language is a system of arbitrary signifiers, even with arbitrary grammatical relationships between the signifiers; but the Language system is rooted upon a foundation of signified objects and referents of common experience.

This foundation is consolidated by the social use of language over time. The system of mutual recognition of signs that make up language rests upon a vast historical social web of acts of communicative experience. The signs we employ when we communicate become an expression of our social history.

The incoherence of a solipsistic language

The problem for solipsism is that without an external reference, both the signifier and the signified referent are arbitrary and even the communicant is arbitrary. There are no fixed points, even the concept of time and therefore memory become arbitrary. The point here is that deprived of fixed points language itself, what language stands for and represents become meaningless. This is a version of the private language argument: not only can solipsism have no coherent language, it has no need for a language, it is essentially meaningless outside its own bubble. It neither makes sense to describe any meaning within solipsism’s impenetrable cell. This does not exactly exclude the possibility of solipsism, but it does exclude solipsism from meaningful discourse. Where we can recognise solipsistic argument, we can recognise expression that lacks meaning beyond a subjective framework.

Communication as the basis for existence and knowledge

Language and communication acknowledges and affirms a reality beyond the solipsistic bubble. Each time we communicate, we assume and express the necessity of an objective, external world. The expressed proposition “I am, I exist” is not only necessarily true in itself, but through the language it employs and the act of communication, it also expresses the necessity of an external reality.

Martin Bennett 2015

Might the y axis be “well I might as well grow my hair to shoulder length while I’m here”?

>The expressed proposition “I am, I exist” is not only necessarily true in itself, but through the language it employs and the act of communication, it also expresses the necessity of an external reality.

Consistent, empirical, shared … but why external?

Or, why not both? Why not internal and external simultaneously? Which is another way of saying what if consciousness is more fundamental than matter and energy?

A theme that permeates the universe (galaxies. smoke clouds, molecules) and our study of it (in art, religion, philosophy, mathematics etc) seems to be “As Above, So Below”. The microcosm, the human scale and the macrocosm. Could “As Above, So Below” also mean “As Internally, So Externally”?

What if God is just a sense of ‘far’ in a world which has forgotten that there in more to life than just ‘near’?

When we imagine ourselves to exist internally, God is ‘out there’, but when we imagine ourselves to exist externally, God is ‘deep within’. When we face North God is that void which exists behind out backs to the South, and vice versa when we face South.

God is over there when we are here, and He is here when we are over there. God is whichever web page is on the tab which is not being currently viewed.

Isn’t God just a perceptual place holder?

And isn’t solipsism just laziness? 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you for responding so quickly. I have realised that I may have to use a different theme for this blog to make it easier to access and respond to.

Solipsism is certainly not laziness. However wrong it appears, it is a disconcerting question that has hung over Philosophy since Descartes. Descartes sidestepped the problem by invoking a higher power that would not allow him to be deceived. His reasoning lacks the rigour of his certainty of his own existence and his God’s existence seems to depend on ideas that Descartes has. Subsequent philosophers have found it hard to explain how or why we can know anything in the public or external sphere. John Locke rejected the idea that there could be anything without experience, but could not satisfactorily deal with Descartes’ doubts about the veracity of experience. George (Bishop) Berkeley agreed that what we know depends on experience (“to be is to be perceived” he said), but said that is all we have. He would have been a solipsist except that he claimed that an omnipresent God made sure that when no one is perceiving, God still does.

This seems to come closest to your conception of God. Having written that, I do not really know what you mean when you refer to God. You could explain further, but I doubt I could ever really know. This goes to the heart of the problem: I have no access to your private experience of yourself or perhaps what you call consciousness. It is clearly important to you, but there is no collective consciousness: I have no idea what it feels like to be you, and if you are like most people, you would bridle if I claimed that I did. The idea that consciousness is more fundamental than matter and energy is truly solipsistic: I would not say that is laziness.

External versus internal is the contrast between public and private. Language, so I have argued, belongs in the public and external sphere. Since we relate to the external, publicly accessible environment we can also use language to rationalise our private experience, but do you not find that private experience precedes language: if you like something, is this feeling language dependent? Is it not a feeling that you then try to put into words (if you feel that you need to).

LikeLike